Guides

Read this if:

You’re a school or district leader who’s being asked:

You don’t need to be an expert in AI. You just need a clear, usable policy, and the tools to roll it out responsibly, equitably, and confidently.

What this guide offers:

Suggested reading paths:

This document hasn’t been procured with a cookie-cutter approach. It’s a practical, flexible playbook you can adapt to your school’s needs — whether you're just starting or refining existing AI norms.

🎓 Note for higher education settings:

While this guide focuses on K–12, many principles apply to universities, colleges, and adult learning institutions. Faculty policies may need to emphasize citation, originality, and research ethics, but the frameworks here still apply to instructional planning, AI transparency, and institutional readiness.

Artificial intelligence has already entered the premises of your school. Your teachers are using it to plan faster. Your students are using it to write smarter. Other schools are being pulled into decisions about tools, ethics, and expectations, often before policies or training are in place.

If your school hasn’t yet created a shared understanding of what “AI in education” really means, now is the time. Because how AI is understood (or misunderstood) across your community directly shapes how it's used, misused, or ignored altogether.

Not all AI tools are created for the same purpose. School leaders need to understand what’s actually happening behind the scenes when a teacher or student uses an “AI tool”. Because this understanding directly informs policy, expectations, and boundaries.

Here’s a breakdown of the four primary categories of AI tools found in school settings, along with examples, benefits, risks, and key policy considerations.

Generative AI refers to systems that create entirely new content, such as text, images, video, code, or audio — based on a user’s input or prompt. Besides curating content, these tools can generate from scratch using large-scale language models (LLMs) and image-generation algorithms.

Here are some examples of Gen AI technology relevant to school use cases:

Common uses in schools:

Benefits:

Risks:

Adaptive AI modifies the learning experience in real-time based on how a student responds. It analyzes input data (like quiz responses or time-on-task) to determine what the student needs next adjusting difficulty, pacing, or content accordingly.

Here are some examples:

Common uses in schools:

Benefits:

Risks:

NLP is a branch of AI focused on understanding and generating human language. It is used in tools that assist with spelling, grammar, translation, speech recognition, and summarization.

Some examples of NLP:

Common uses in schools:

Benefits:

Risks:

AI is also increasingly being used behind the scenes in school operations. It can help leadership teams make decisions about enrollment, scheduling, staffing, or budgeting through data analysis and predictive modeling.

Here are some technology examples and their use cases:

Benefits:

Risks:

Before any policy is written, it’s important to understand the difference between instructional AI and institutional AI.

While both need policy oversight, this guide focuses on classroom-facing AI tools — particularly generative AI used for teaching, learning, and assessment.

A policy written without shared understanding won’t stick.

You cannot expect teachers and educators to follow guidelines that they don’t understand. Students won’t follow rules they don’t believe are fair. And admins can’t enforce policies if their teams can’t distinguish between helpful tools and harmful shortcuts.

That’s why, among staff, students, and even families, AI literacy is the foundation for any responsible implementation. This means:

Start by creating a common understanding of generative AI through structured literacy efforts before writing a policy.

In the absence of clear guidelines, most teachers are doing what educators always do: experimenting, adapting, and sharing ideas with their peers. Now that AI is a part of the picture, the result is a highly uneven landscape across schools and even departments:

This “quiet adoption” of AI is already affecting teaching, learning, and assessment, even in schools without formal guidance.

As school leaders, you don’t need to become AI experts. But you do need to create the conditions for safe, equitable, and effective use. That means establishing a common foundation now, before the tools go further ahead than your policies.

The aim of this chapter is to get everyone on the same page educationally (not technically).

The next chapter will explore why having a school-wide AI policy is not just recommended.

When generative AI entered the classroom through tools like ChatGPT, many schools did what they’ve done with previous waves of education technology: observe first, act later.

But unlike interactive whiteboards, learning apps, or even LMS platforms, AI isn’t a standalone tool or a single-use upgrade. It’s a systems-level shift that changes how students learn, how teachers plan, and how schools operate.

And it’s already happening.

Teachers are using generative AI to create lesson plans, reading passages, quizzes, and parent communications. Students are submitting AI-written essays and running their own prompts in parallel to classroom instruction. Support staff are relying on AI-powered chatbots to streamline administrative communication.

It’s already embedded in your school — the only question is whether your leadership team has addressed it with the clarity and intentionality it deserves.

That’s what an AI policy is for. Not to regulate novelty, but to protect what matters most: instructional quality, academic integrity, staff wellbeing, and student safety.

In conversations with school leaders around the world, a pattern has emerged:

“We know we need an AI policy. We just don’t want to rush it or get it wrong.”

This hesitation is understandable. But avoiding a policy doesn’t avoid the impact. It simply delegates the decisions to individual classrooms, often without support.

Without policy, AI adoption happens quietly, unevenly, and under the radar. And that opens up several systemic risks:

In the absence of guidance, teachers self-regulate. As a results, the results vary widely: one teacher may fully embrace AI to help differentiate instruction for multilingual learners, another may ban it outright for fear of enabling student shortcuts. Meanwhile, a third might be unaware that their colleagues are even using it.

This creates a fractured learning experience where students have unequal access to tools, supports, and expectations depending on the classroom they walk into.

This undermines one of the core goals of any instructional leadership team: coherence. A policy, here, will ensure that innovation happens within a shared framework.

Ironically, when schools avoid policy to keep things “open,” they actually create more confusion and more work for teachers.

Consider a scenario where a teacher wants to use AI to speed up their lesson planning. Without clear guidelines, they may spend hours researching which tools are allowed, second-guess what data they’re permitted to input, hesitate to share their workflows with peers or leadership, or avoid AI altogether.

Here, a policy will reduce decision fatigue by giving teachers confidence in the boundaries and support to try new tools safely.

AI, if not implemented thoughtfully, can exacerbate existing inequities. Consider:

A policy might not solve all equity challenges, but it can set clear expectations that reduce variance, ensure scaffolding, and promote thoughtful access.

Let’s be honest: most students now know how to use AI to do their work and many are using it regularly, especially in unmonitored environments like homework or take-home assessments.

But without a policy, teachers are left to guess things like if AI-assisted writing should be permitted or if doing so is considered cheating.

A lack of clarity erodes trust between teachers and students. A good policy invite open conversation around AI’s role in learning and hold everyone to the same shared standard.

Generative AI tools often require users to input text that may include student data, work samples, or sensitive information. But most tools were not built for K–12 compliance and terms of service rarely guarantee the level of data protection required by regulations like FERPA, COPPA, GDPR, or state-level equivalents.

If a teacher pastes a student’s IEP goal into ChatGPT to generate support materials, that may violate privacy laws, expose PII (personally identifiable information) to third-party systems, and breach internal tech use policies.

An AI policy offers clear, proactive boundaries around data input, storage, and platform vetting, helping schools stay audit-ready and legally compliant.

The core reasons are:

Here’s what a well-written, living AI policy enables:

At the end of the day, an AI policy should protect your teachers, support your students, and reflects your school’s values in the face of rapid change.

Generative AI can help address common challenges in teaching, such as resource overload, time constraints, and differentiation. They do this by offering a structured, teacher-directed workflow. When thoughtfully integrated, these tools can align with school values and policy standards.

Here’s how they typically fit into classroom use:

Because of this, generative AI tools can be incorporated into policy under categories like:

These tools are most effective when they support, not replace, professional judgment.

You don’t need to have all the answers to start building a policy. What you need is a clear reason to act and that reason is here:

A good AI policy will give them the structure to try those things safely, ethically, and effectively.

The first step of having creating effective policies is having a set of foundational principles. Without this, any policy risks becoming performative or outdated the moment a new tool enters the market. But when grounded in clear, forward-thinking values, your policy can adapt, evolve, and actually serve the people it’s meant to support.

In this chapter, we’ll walk through the six foundational principles of effective AI guidance drawn from real school needs, instructional research, and the current behavior of staff and students across K–12 environments.

This is the most important principle your policy can establish and it should be explicitly stated. Regardless of how advanced or accurate a tool appears to be, o generative tool can replace pedagogical insight, relationship-building, or the ability to respond to student needs in real time.

Just because a tool is new doesn’t mean it’s necessary. Strong policies help leadership teams assess AI not based on trendiness, but on instructional relevance. If it doesn’t enhance clarity, efficiency, or inclusivity in learning, it doesn’t belong in your system.

While AI offers powerful potential to differentiate instruction, it also risks widening gaps if access is inconsistent or tools are not designed for diverse learners. Effective guidance acknowledges this and builds inclusion into its usage expectations.

If a teacher uses AI to create reading passages, students should know. If students use AI for drafting ideas, they should disclose that use. And when leadership teams use AI for decision-making (e.g., forecasting, scheduling), those processes should be transparent.

A modern AI policy acknowledges that student misuse is more of a design issue than discipline. If assignments can be easily completed by ChatGPT, the question isn’t just “How do we stop students from using it?”. It’s “Why does this task allow for such shallow learning?”

The best AI policies are co-authored with staff, introduced slowly, and supported with ongoing opportunities for learning and reflection. A launch-and-forget approach won’t work, especially if most educators are still developing their own understanding of AI.

When policies are rooted in values like transparency, inclusion, and teacher judgment, they do more than set rules. They help schools build a system that’s thoughtful, adaptable, and ready for real change.

In the next chapter, we’ll move from principles to practical steps: how to form a task force, audit your current usage, and begin building a custom AI policy that reflects your school’s specific context.

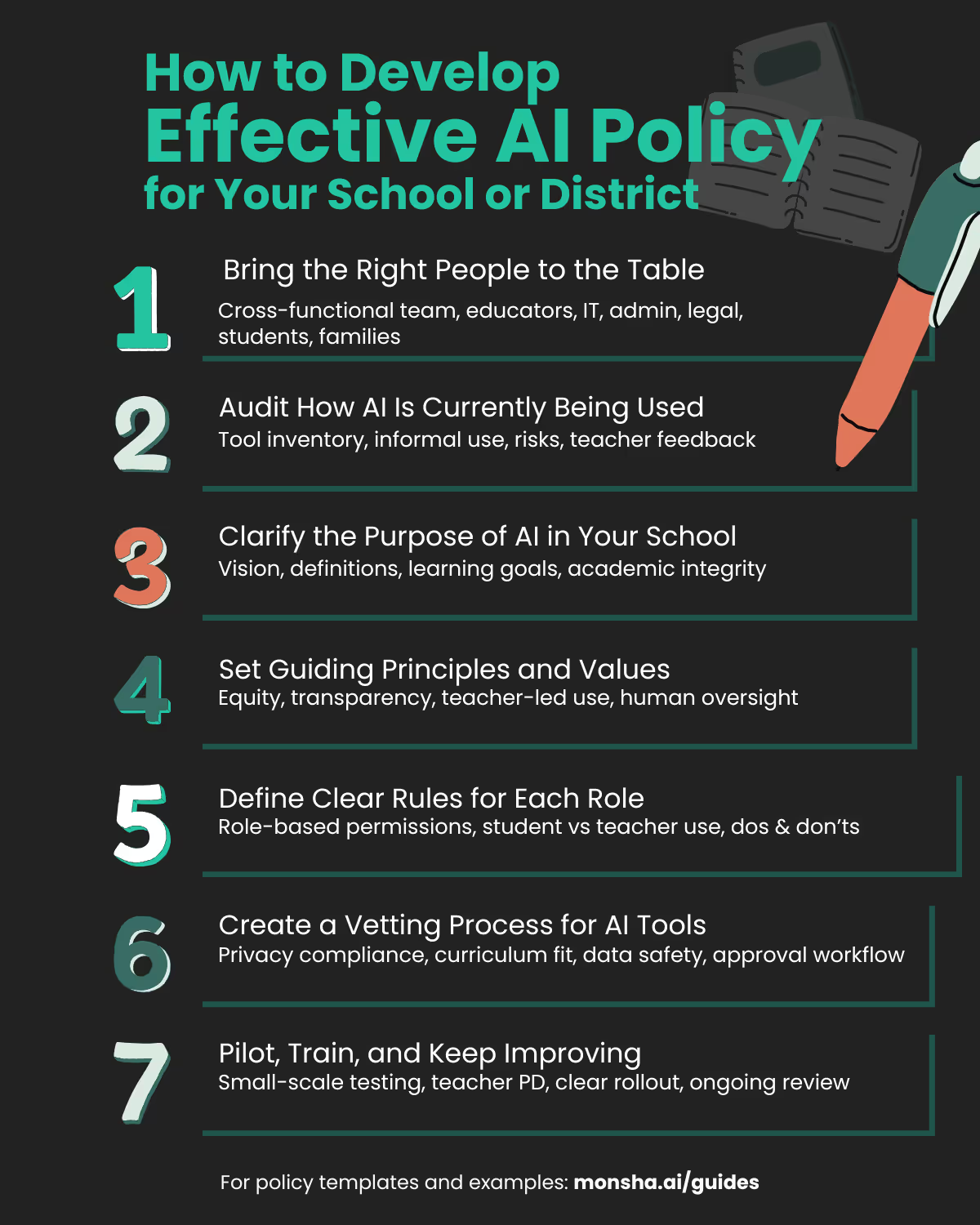

Below we have detailed a structured, step-by-step path for building a usable, school-wide AI policy that supports clarity, consistency, and instructional trust. It ends with how to scale this work to the district level.

AI use touches every part of a school: instruction, IT, compliance, assessment, and equity. In such a situation, policies built in isolation will fail because they miss how tools actually show up in classrooms.

What to do:

Pro tip: Treat this group as a task force or working group, not a committee, to emphasize this is action-oriented and time-bound.

Most schools already have AI in the building. Hence, before moving forward with policy creation, it is important to take notes of the current usage of AI by the stakeholders. This includes teachers, students, parents and other staff.

What to do:

Teachers, students, and support staff all use AI differently. Without role-specific guidance, you risk confusion, inconsistency, or overreach.

What to do:

Pro tip: Use real examples and scenarios from your audit. The more grounded your guidance, the easier it is to adopt.

Not all AI tools meet the same standard for safety, clarity, or usefulness. Without a vetting process, you risk privacy violations, poor-quality outputs, or tools that don’t align with your values.

What to do:

Piloting allows you to test your policy, your training, and your tools in a safe way. It also builds internal champions who can help scale adoption later.

What to do:

Pro tip: Pilot data = buy-in. Share time saved, student outcomes, or teacher quotes during the full rollout.

Policies only work when they’re clear, accessible, and consistently applied. A 12-page document that no one reads helps no one.

What to do:

Pro tip: Frame this as professional trust, not surveillance. Emphasize how the policy supports teachers in planning and reduces ambiguity for students.

AI will evolve. So will your policy. Setting a review cycle helps normalize updates and ensures your guidance stays useful.

What to do:

Pro tip: Treat your AI policy like your assessment or curriculum frameworks. Treat them more like living documents, not static rules.

Once a single school has developed and tested its policy, district or network leaders can build from that momentum.

Here’s how district leaders can scale responsibly:

Districts that focus on clear expectations and shared tools, while giving schools room to adapt, see stronger adoption, better alignment, and more sustainable implementation.

The biggest mistake schools make when developing AI policy is waiting too long to start. There is no perfect policy. But the cost of silence or inaction is already showing up in classrooms, assessments, and parent conversations.

Start with what you know. Build with the people you trust, pilot what you draft, and let your school grow into its own version of responsible AI use — grounded in equity, instructional quality, and trust.

Once your leadership team are aligned on the core principles and piloted responsible use cases, the next step is to formalize your work into a document that can guide the entire school community.

You don’t want your AI policy to read like a legal contract. It should help teachers and students feel confident, not constrained — while being adaptable enough to evolve with the tools themselves.

This chapter breaks down the essential components your policy document should include, along with examples and formatting suggestions to help you get started.

Start by explaining the objective behind having a policy in the first place. Teachers, students, and parents will all approach this document with different assumptions. However, many schools make the mistake of diving into dos and don’ts without grounding the reader in context. This section is your chance to unify them.

What to include:

Here’s an short example with the most common reasons we have seen:

This policy has been developed to guide the safe, ethical, and educationally effective use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools in our school community. As AI becomes increasingly present in classrooms, our goal is to ensure that its use enhances learning, supports teachers, and upholds academic integrity. The policy offers clear expectations for students, staff, and families, and will be revisited regularly as new tools emerge.

The objective behind having this section is to create a shared language. Many misunderstandings around AI happen because people are working from different mental models. Keep your definitions short and accessible. Note that this section isn’t for technical jargon, but for practical clarity.

Key terms to define:

Your policy should be grounded in values, not just rules. This section should outline the educational philosophy that underpins your approach to AI. These principles can later be referenced when reviewing new tools or handling edge cases.

Principles to consider including:

Framing this section helps your school move away from reactive rule-setting and toward proactive, thoughtful implementation.

Clarity helps to increase adoption. This section should break down expectations for different groups in your school community. Avoid blanket policies. Instead, describe what appropriate use looks like for each role.

You can use a table format, scenario examples, or side-by-side dos and don’ts.

Here are some examples for all stakeholder involvement:

For teachers:

For faculty and instructors:

For academic support teams:

For students:

For administrators:

This section should detail how new AI tools will be evaluated and approved. It helps prevent reactive decisions and gives teachers a clear pathway to request or propose platforms that support their practice.

Try including:

Optional: Maintain a living list of approved and prohibited tools, reviewed at regular intervals.

You may already have a general digital use policy for students. This section can either live within that or serve as an AI-specific extension. The key to implementation of this section is clarity.

Include:

Families and staff need to know their information is safe and that your school takes data protection seriously. Many generative AI tools store user input or require access to third-party platforms, which can raise privacy concerns if left unchecked.

What to clarify in this section:

Include links to your existing data use or digital citizenship policies to reinforce consistency.

In postsecondary settings, faculty and researchers must avoid inputting thesis drafts, research data, or unpublished manuscripts into generative AI tools without approval, as this may conflict with intellectual property, IRB, or publishing guidelines.

Your AI policy should empower your staff with support systems and clear expectations and be framed as a shared agreement, not a surveillance document. The objective behind having this section is to ensure that.

This section should answer:

Approach this section with a growth mindset tone . At the end of the day, it’s about building trust, not enforcing perfection.

AI tools and the laws that govern them are evolving quickly. To make your policy effective, treat it like a living document by reviewing and revising it regularly. The best way to ensure that would be to create a policy on executing it altogether.

What to include:

The strongest AI policies come with tools people can actually use. These supporting materials help your staff move from theory to practice and ensure the policy is accessible to everyone it impacts.

What to attach or link to:

An AI policy should be a shared understanding of how your school community will explore new tools while protecting what matters most: student learning, educator trust, and equitable access.

As you move toward implementation, remember that the document is only the beginning. What comes next i.e., training, communication, iteration — is what determines whether your policy becomes part of your culture or stays on a shelf.

Creating a policy is only the beginning. For it to matter, your staff needs to understand it, believe in it, and feel equipped to apply it. That won’t happen through a mass email or a policy PDF uploaded to your intranet.

Responsibly introducing AI into a school system requires a thoughtful approach to professional learning, change management, and trust-building. Many teachers are still navigating what AI is, let alone how to use it ethically or effectively. Others may have already experimented with tools and now need structure to scale that use with confidence.

This chapter explores how to support educators not just in knowing your AI policy, but in living it through hands-on training, collaborative exploration, and low-pressure opportunities to try, reflect, and grow.

No two teachers will arrive at AI from the same place. Some are eager and already experimenting. Others are cautious, skeptical, or concerned about workload and ethics.

Before rolling out any training, start by understanding the landscape.

Questions to consider:

Use informal polls, department-level conversations, or quick check-ins to gather insights. This will help you shape support that’s relevant, not redundant.

In postsecondary settings, faculty and researchers must avoid inputting thesis drafts, research data, or unpublished manuscripts into generative AI tools without approval, as this may conflict with intellectual property, IRB, or publishing guidelines.

One of the reasons many teachers feel intimidated by AI tools is the myth that they require technical expertise or creative prompting. That might be true for general-purpose tools like ChatGPT. But classroom-ready tools built for educators should not require coding knowledge, AI training, or hours of experimentation.

In fact, the best AI tools for education:

Training should reflect this reality: AI in schools is not about turning teachers into technologists. It’s about helping them do what they already do — faster, more inclusively, and with more time for student engagement.

The most successful professional development around AI doesn’t just deliver information. It creates safe spaces for dialogue, exploration, and honest reflection. Consider these principles when designing your rollout.

1. Lead with relevance, not risk

Avoid framing AI solely through the lens of cheating, fear, or monitoring. Instead, lead with what teachers care about: saving time, improving differentiation, and engaging students.

Examples:

Focus sessions on real tasks teachers already do and how AI can support them without adding complexity.

2. Embed PD into existing structures

Rather than adding entirely new PD days or optional webinars, integrate AI training into what your school already does:

Make sessions short, hands-on, and connected to the immediate work teachers are doing.

3. Model, don’t just mandate

Teachers learn best from each other. Peer modeling is one of the most powerful forms of professional development, especially with emerging tools.

Ways to model responsible AI use:

This turns training from demonstration into co-creation and builds a culture of shared experimentation.

4. Offer entry points for different comfort levels

Your staff will likely fall into three groups:

Avoid one-size-fits-all training. Offer parallel sessions like:

You might also consider creating a short self-paced module or PD slide deck teachers can explore independently.

Once the policy is rolled out and training sessions are complete, educators need ongoing pathways to revisit, ask questions, and adapt.

Ways to sustain learning:

Encourage a culture of reflection and iteration. As teachers grow in confidence, they’ll shape how the policy lives in practice.

Not everything has to scale at once. Pilots can serve as both training and feedback loops.

Try piloting:

Document the process. Gather insights. Use these to adjust your expectations, identify further training needs, and highlight early wins.

As policies are implemented, school leaders will inevitably face cases of confusion, misuse, or pushback. When this happens, accountability should be framed as part of the learning process — not a punitive response.

The goal is trust, clarity, and a system that supports your staff as they adapt to a changing instructional landscape.

When school leaders hear about AI, they often ask: “But what does this actually look like in a real classroom?”

Policies, tools, and principles all matter, but implementation lives and dies in the details of day-to-day practice. That’s why it’s critical to explore how educators are actually navigating AI-supported instruction, both successfully and not.

This chapter presents a set of representative, hypothetical case studies based on the challenges schools are facing today. They show what responsible use can unlock and what can go wrong without structure, support, or shared expectations.

Note: All of the following are representative use case inspired by real educator workflows.

Ms. Rivera, 5th Grade Teacher | Title I Elementary School | California

Ms. Rivera teaches a diverse class where nearly a third of her students have IEPs or receive reading intervention services. She spent hours each week manually rewriting texts, adjusting materials for different Lexile levels, and reformatting activities to support co-teachers during push-in support.

To make planning more manageable, she started using a curriculum-aligned platform that allowed her to:

By the end of the first month, she was saving 4–6 hours per week on planning and differentiation. More importantly, she felt less reactive and more confident her materials were inclusive by design — not just patched together.

“Instead of planning for the middle and fixing later, I can now plan for everyone from the start.”

Note: This is a representative use case inspired by real educator workflows.

Mr. Patel, High School English Teacher | Private International School | Singapore

Midway through the term, Mr. Patel discovered that several students had used generative AI tools to write large portions of their essays. There were no clear policies in place, and when he raised concerns, students replied that they thought it was “like using a calculator, but for writing.”

The school had previously avoided formal AI guidance, hoping to buy time and “see how it plays out.” But without expectations, confusion took over:

The issue escalated when parents got involved, asking why their children were being penalized for using tools that hadn’t been explicitly prohibited.

After this, the school formed a task force to:

“What started as a policy gap became a trust gap. It reminded us that silence around new tools is still a message and not a helpful one.”

Note: This is a representative use case inspired by real workflows.

Dr. Alvarez, Director of Teaching and Learning | Charter Network | Texas

Dr. Alvarez oversees curriculum across five K–8 campuses. She had been hearing the same concerns from every principal: lesson quality varied dramatically across classrooms, differentiation was inconsistent, and teacher planning time was ballooning under pressure.

After evaluating several options, her team rolled out a unified instructional planning system that enabled:

Rather than forcing a single curriculum, the platform gave schools shared structure while preserving teacher choice.

Within one term:

Dr. Alvarez emphasized that it wasn’t just the tool — it was embedding it into existing planning cycles, walkthroughs, and coaching sessions that made it stick.

Note: This is a representative use case inspired by real educator workflows.

Artificial intelligence already exists in schools. Your instinct can be to delay, to wait for more research, or to see what other districts do. But silence is still a signal. When school leaders don’t offer clarity, they leave staff and students to fill in the gaps themselves — often inconsistently and unethically.

This guide is to help your educators, learners, and families have a shared language, a transparent policy, and the confidence to move forward with trust.

You don’t have to become an AI expert. You do have to protect instructional quality. You do have to plan for equity, not just efficiency. And you do have to create the conditions where teachers and students can use new tools thoughtfully, responsibly, and effectively.

As you implement your own policy, remember:

With the right leadership, AI can become a powerful support system — one that frees your teachers to focus on students, helps your school serve all learners better, and prepares your community for the world that’s already here.

Academic Integrity

Upholding honesty in learning by setting clear expectations around student authorship, citation, and appropriate tool use — including AI.

Academic Publishing Ethics

Standards that guide how scholars cite, attribute, and use external tools (including AI) in research and teaching.

Adaptive Learning AI

AI tools that adjust instruction in real-time based on how a student responds, creating personalized learning paths.

AI Detection Tools

Software that attempts to identify if a piece of writing was generated by AI. These tools often have high false positive rates and are not fully reliable.

AI Hallucination

When an AI tool generates false, misleading, or inaccurate information that sounds plausible but isn’t factually correct.

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Technology that allows machines to perform tasks that typically require human intelligence, such as generating text, and images, or making predictions.

COPPA (Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act)

A U.S. law that restricts data collection from children under 13 and governs how schools manage digital privacy.

Editable Output

AI-generated content that the teacher can review, modify, and customize before using in class — considered essential for responsible use.

FERPA (Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act)

A U.S. law that protects the privacy of student education records.

GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation)

A European Union regulation that governs data privacy and protection, with implications for international schools and tools used globally.

Generative AI

A type of AI that creates new content — such as text, images, or video — based on a prompt. Examples include ChatGPT, Canva Magic Write, and AI-powered lesson planning tools.

IEP (Individualized Education Program)

A personalized learning plan designed for students with disabilities, outlining goals, accommodations, and support services.

Instructional Alignment

Ensuring that AI use supports the school’s curriculum goals, standards, and teaching philosophy — rather than adding unrelated complexity.

IRB (Institutional Review Board)

A body that oversees research involving human subjects; relevant when AI tools are used for analysis involving student data.

Living Document

A policy or plan that is regularly updated as new tools, use cases, or regulations emerge.

Natural Language Processing (NLP)

A field of AI focused on enabling machines to understand and generate human language. Used in tools like speech-to-text, Grammarly, and AI chat assistants.

Personally Identifiable Information (PII)

Any information that can identify a specific student or staff member, such as names, birthdates, grades, or IDs.

Prompt

An input or instruction is provided to an AI tool to generate a specific output. For example, “Create a lesson plan on photosynthesis for 6th grade.”

Tool Vetting

The process of evaluating whether an AI tool is safe, instructionally aligned, and compliant with privacy laws before allowing it in classrooms.

An AI policy helps schools set clear expectations for how artificial intelligence can support teaching and learning. It also safeguards student and staff privacy and protects academic integrity.

AI should be used to enhance instruction, such as generating differentiated resources, automating routine planning tasks, or supporting personalized learning, while always keeping the teacher in control.

Policies should clearly outline which users e.g. students, teachers, and staff are permitted to use AI, and under what circumstances.

Ethical AI use means ensuring tools are used transparently, responsibly, and without replacing human judgment. Materials generated by AI should always be reviewed by educators before use.

Schools can use LMS usage logs, feedback loops, and periodic reviews to monitor how AI is being used and whether it aligns with policy expectations.

Yes. A school might have one unified policy or allow departments to create their own guidelines, as long as they align with the school’s broader ethical and instructional vision.

In many cases, yes — especially if the tool collects or stores personally identifiable information. Policies should address this clearly to ensure compliance with privacy laws like FERPA and COPPA.

Policies may outline instructional responses, guidance, or appropriate disciplinary actions for misuse — while also emphasizing that most misuse stems from misunderstanding, not intent.

Join thousands of educators who use Monsha to plan courses, design units, build lessons, and create classroom-ready materials faster. Monsha brings AI-powered curriculum planning and resource creation into a simple workflow for teachers and schools.

Get started for free